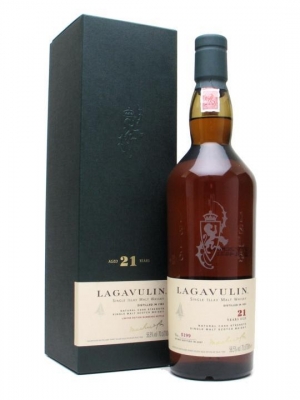

Lagavulin 1985/2007, 21 yo OB, 56.5%

Post number 100! Something special then.

I have quoted the William Black quote found on Lagavulin bottles before, but I’ve also often wondered what the original source material was. Today I actually did some research – ‘The Strange Horse of Loch Suainabhal’ is a tale written by William Black in ‘Lady Silverdale’s Sweetheart and Other Tales’, published in London by Sampson, Low, Marston & Company. No date is found but it was re-published in the New York Times on 2nd January 1876, suggesting the original publishing date must have been earlier. A digital copy of the New York Times story is available today here.

Loch Suainabhal

It is a fictional letter, addressed to a lady (Ms Mackenzie) living in Hyde Park Gardens, London by Alister-nan-Each, of Borvabost, in the island of Lewis, Hebrides, and consists of a man’s frightened recounting of his encounter with a creature on the shore of Loch Suainabhal ( Suinabhal, Suainaval). The protagonist Alister agrees to accompany Aleck Cameron to Uig from Dugald MacKillop’s farm, with nothing more than a bottle of Lagavulin in his coat pockets. Along the way, it is discovered that Aleck Cameron, despite being endowed with a fiery disposition, does not appreciate strongly flavoured whisky himself and turns back to the farm to retrieve his own ‘Campbelton’ whisky. Alister determines to make it to Uig before Aleck nonethless and travels down the road by Loch Suainabhal alone. As he passes close to the shore of the loch, he encounters a strange creature the size of six or more seals, with a head and eyes thrice the size of a horse’s, but without ears or horns, and covered in shiny black scales. The greatest tragedy then unfolds, as Alister drops and breaks his only source of courage, his bottle of Lagavulin, thereby alerting the beast to his presense, and causing it to return to the water with a great noise.

The most dramatic section of the text:

It waz about the o’clock, or maybe it waz six o’clock, or half past fife, and not much more dark as it waz the verra middle of the loch going along by the side of Suainabhal; and I will put my hand down on the Bible itself and I will sear I waz as sober as any man could be. Sober, indeed! – is it to be trunk to trink a glass at a marrach? … Now, Miss Sheila, this is the whole story of it; that the watter in the loch was verra smooth, and there waz some clouds ofer the sky; but everything to be seen as clear as the tay. And I waz going along py myself, and I waz thinking no harm of any one, not efen of Aleck Cameron, that waz away back at the farm now, when I sah something on the shore of the loch, maybe four hundred yards in front of me, and it waz lying there verra still. And I said to myself, “Alister , you must not be frightened by anything; but it is a stange place for a horse to be lying upon the stones.” And he did not move one way or the other way; and I stopped and I said to myself, “Alister, it is a stranche thing for a horse to be lying on the stones, and there is many a man in the Lews would be frightened, and would rather go back to Dugald MacKillop’s farm; but as for you, Alister, you will just tek a drop of whisky, and you will go forward like a prave lad and see whether it is a horse, for it might be a rock mirover, aye, or a black cow.” So I will go on a bit; and the black thing it did not move either this way ot that; and it I will tell you the truth, Miss Sheila, I was afraid of it, for it waz a verra lonely place, and there waz no one within sight of me, nor any house that you could see. And this waz I said to myself, that I could not stand there the while night, and that I will either be going on by the beast or be going pack to Dugald MacKillop’s farm, and there they would not belief a word of it, and Aleck Cameron, he will say I would be for going pack after him and his Cambleton whisky. And I said to myself, “Alister, you are beginning to tremple; you must tek a glass of whisky to steady yourself, and yo uwill go forward and see what the beast is.”

It waz at this moment, Miss Sheila, as sure as we hef to die, that I sah it mofe its head, and I said to myself, “Alister, are you afrait of a horse, and is it a black horse that wil mek you stand in the middle of the road and tremple?” But I could not understand why a horse will be lyng on the stones, which is a stranche thing. And I said to myself, “Is it a seal you will be seeing far away along the shore?” But whoever will hear of a seal in fresh watter; and mirover, it waz as pig as six seals or more az that. And I said to myself, “Alister, go forward now, for you will not hef a a man like Aleck Cameron laughing at you and him as ignorant as a child about the Lagavulin whisky.”

Now , I will tell you, Miss Sheila, apout the terrable thing that I sah; for it waz no use thinkin’ about going pack to the farm : and I will go forward along the road, and there waz the bottle in my hand, so that if the beast came near I could break the bottle on the stones and gife him a fright. But when I had gone on a piece of the road I stood still, and all the blood seemed to go out of my body, for no mortal man efer sah such a terrable thing. It waz lying on the shore – ay, twelve yards or ten yards from the watter – and it waz looking down to the watter with a head as pg as the head of three horses. There waz no horns or ears to the beast, but there waz eyes bigger as the eyes of three horses, and the black head of it waz covered with scales like a salmon. And I said to myself, “Alister, if you speak or mofe you are a dead man; for this ahfu crature is a terrable thing, and with a bound like a teeger he will come down the road.” I culd not mofe, Miss Sheila; there was no blood left in my body, and I could not look this way or that for a rock or a bush to hide myself, for I waz afrait that the terrable beast would turn his head. Ay, ay, what I went through then no one can efer tell; when I think of it now I tremple; and yet there are one or two that will belief the foolish lies of John the Piper, that is in himself the verra trunkenest man in all the Island of Lews.

It was a stanche thing, Miss Sheila, that I tried to whesper a prayer, and there waz no prayer would come into my head or to my tongue, and instead of the prayer mirover, there waz something in my throat that waz like to choke me. And I could not tek my eyes from the terrable head of the beast; but now when I hed the time to think of it, I belief the pody of it waz black and shining, but with no hing feed at all but a tail. But I will not sweer to taat whatever; for it is no shame to say that I waz templing from the crown of my head down to the verra soles of my feet, and I waz watching his head more as the rest of his body, for I did not know when he might turn rouns and see me standing in the road. Them that sez I sah no such thing, will they tell me how long I stood looking at him? Ay, until the skies waz darker over the loch. Gott knows I would hef been glad to hef seen Aleck Cameron then, though he is a verra foolish man; and it waz as many a time I will say to myself, when I waz watching the beast. “Alister, you will nefer come by Loch Suainabhal by yourself again, not if you waz living for two hundred years or fife hundred years.” And how will John the Piper tell me that – that I waz able to stand there in the middle of the road? Is it trunk men that can do that? Is it trunk men that can tell the next morning, and the morning after that, what they hef seen? But you know, Miss Sheila, that there is no more sober man az me in all the island; and I will not pother you any more with thpse foolish lies.

And now an ahfu thing happened. I do not know how I am alife to be writen the story to you this day. I waz telling you, Miss Sheila, that there waz little thought among us of sleeping for five or six nights before; and many of the nights waz verra wat; and I think it might hef been on board of the big steamer that I willget a hoast in my throast. And here, az I waz standin in the road, fearful to mek the least noise, the koff came into my throat; and I trempled more than efer for fear of the noise. And I struggledl but the koff would come into my throat; and then thinks I, Alister, Gott’s will be done; ad the noise of the koff frightened me; and at the same time I tropped the bottle on the stones with the fright, and the noise of it –never will I forget the noise of it. And at the same moment the great head of the beast it will turn round, and I could stand up no more; I fell on my knees, and I tried to find the prayer, but it would not come into my head – ay, ay, Miss Sheila, I can remember at this moment the ahfu eyes of the beast as he looked at me, and I said to myself, Alister, you will see Borva no more, and you will go out to the feshen no more, and you will drink a glass no more with the lads come home from the Caithness feshen.

Then, az the Lord’s will be done, the stranche beast he turned his head again, and I sah him go down over the stones, and there waz a great noise of his going over the stones, and I waz just as frighted as if he had come down the road, and my whole body it shook like a reed in the wind. And then, when he had got to the watter, I heard a great splash, and the watter was splashed white apout him, and he went out from the shore, and the last that I sah of the terrable crayture waz the great head of him going down into the loch.

Here Black’s beast is described in the fashion of a ‘kelpie’ or water horse, as such creatures were imagined at the time. Scots are no stranger to such tales and many of Scotland’s large lochs have an association with cryptids, the most famous today being Loch Ness and Nessie, in whose incarnation the supernatural has given way to fantastic science in the guise of a surviving dinosaur. As for Black’s words, I can only imagine when it made it to the label – for instance they were already on 70s white label bottles, a picture of a 50s bottling I’ve seen also has the quote.

I have made several posts on Lagavulin, but I do not think I have described its history before. We owe Lagavulin to John Johnston and Archibald Campbell. The year the distillery was founded in is incorporated into the bottle design – 1816, a year after its two equally famous neighbours. Lagavulin’s site was shared with two other distilleries in its history. From 1817 to 1835, Ardmore distillery ran often under the name of Lagavulin 1 or 2 (we are unsure, likely 2), and from 1908 to 1960, Malt Mill existed as proof of Peter Mackie’s vindictiveness.

Ardmore Distillery 1817 to 1835

Sources are unclear if it was John or Archibald or both together who founded Ardmore, and whence it became known as Ardmore as opposed to its later name of Lagavulin 2. It started off as a 92 gallon, single wash still distillery which was expanded into regular double distillation with a 30 gallon low wines still (source). By 1836, Johnston had died and having owed a sum to Alexander Graham of Islay Cellar £1103 9s 8d, Lagavulin passed to him. A valuation was carried out, showing Still House no.2, Tun room and Malt Barn no.4 as belonging to Ardmore, and owned by Laird Waler Frederivk Campbell. Alexander promptly acquired Ardmore as well, and merged it into one Lagavulin distillery.

Lagavulin came into the possession of John Crawford Graham in 1852, and then James Logal Mackie in 1867. James then hired his to-be-famous nephew Peter Mackie in 1878 and he took over managment after James’ passing in 1889.

Malt Mill 1908 to 1960

Malt Mill is clearly famous despite its long demise, even being the subject of a whole movie ‘The Angels’ Share’ two years ago. Most would know the tale – Peter Mackie was also the sole sales agent for Laphroaig, and when Laphroaig decided to manage their sales themselves, Peter retaliated by first suing, and when he lost, he dammed up Laphroaig’s water source and so ended up in court again. After he was ordered to remove the dam, he changed tactics and attempted to buy over Laphroaig. When that too failed, he capitalised on his familiarity with Laphroaig and built Malt Mill as an exact copy of Laphroaig’s spirit, but that was doomed to fail. It is no simple task copying a distillery’s spirit, even when it’s just next door.

And so Malt Mill chugged on till 1960, producing a spirit which according to those who have actually tasted it was ‘far too heavy’. 6 bottles of its newmake remains in a cupboard in Lagavulin, from the last run in 1960. Lagavulin was rebuilt in 1962, and it was then that Malt Mill lost its equipment, and was turned into Lagavulin’s visitor centre. Malt Mill’s stills were moved to Lagavulin and used for another seven years till 1969. If you were drinking Lagavulin bottled in the 70s or early 80s, there’s a good chance some of it was made with these stills.

These stills were replaced in 1969, and the new ones were now steam heated. The floor maltings went in 1974, and then on Port Ellen next door provided the malt. As Peter Mackie’s White Horse Distillers had already been acquired by DCL in 1927, Lagavulin simply passed down to modern Diageo. Lagavulin today is running at absolute full capacity due to demand, and is one of the only distilleries whose malt goes almost entirely to single malt bottlings and not blends. Most Lagavulin isn’t even matured on Islay warehouses, being shipped off the the mainland instead.

Lagavulin 1985/2007, 21 yo OB, 56.5%

Noteworthy mention: When released this was described as being from 100% Spanish oak sherry butts, and the last such bottling available.

When I tasted this I had a small amount of the regular 16 as a ‘control’.

Nose: Without dilution, the nose is huge as expected. Immediately struck by the thickness and unctuousness of the sherry. It is full and ripe with a creamy cheesy ripeness, with quite a bit of farmyard thrown in. Otherwise the basic profile is recognizable immediately: The dry but rich smoke, the salt, the seaweed, and the balance. The peat here is huge too, beyond the 16. But that’s not a fair comparison isn’t it. Ok, menthol and a crushed leafy oil vegetal-ness, like sour greengages but it’s hard to pin down. Dry tobacco leaf, wet wool/salty rope, and hardened scented wax.

Nose: Without dilution, the nose is huge as expected. Immediately struck by the thickness and unctuousness of the sherry. It is full and ripe with a creamy cheesy ripeness, with quite a bit of farmyard thrown in. Otherwise the basic profile is recognizable immediately: The dry but rich smoke, the salt, the seaweed, and the balance. The peat here is huge too, beyond the 16. But that’s not a fair comparison isn’t it. Ok, menthol and a crushed leafy oil vegetal-ness, like sour greengages but it’s hard to pin down. Dry tobacco leaf, wet wool/salty rope, and hardened scented wax.

Palette: Huge again, all the stuff that makes it a Lagavulin, but also more menthol, more farmy ripeness, and something really similar to old bottles, but more ‘wet’ and leafy. It has its sweetness and plum paste with this skins in for tannin matched with thick peat and resinous peat oil. Continues to evolve on the tongue, displaying great depth and increasing saltiness.

Palette: Huge again, all the stuff that makes it a Lagavulin, but also more menthol, more farmy ripeness, and something really similar to old bottles, but more ‘wet’ and leafy. It has its sweetness and plum paste with this skins in for tannin matched with thick peat and resinous peat oil. Continues to evolve on the tongue, displaying great depth and increasing saltiness.

Finish: Long, salty, peatsmoke, sour fruit, salivatingly moreish.

Finish: Long, salty, peatsmoke, sour fruit, salivatingly moreish.

A joy. Huge complexity with huge development on the nose and tongue. The Lagavulin style we know is all there, but showing off old style angles with gusto, all the while reveling in its colossal sherry – peat 1-2 punch.